[Dear readers: This issue contains discussions of sexual assault, suicide, and more.]

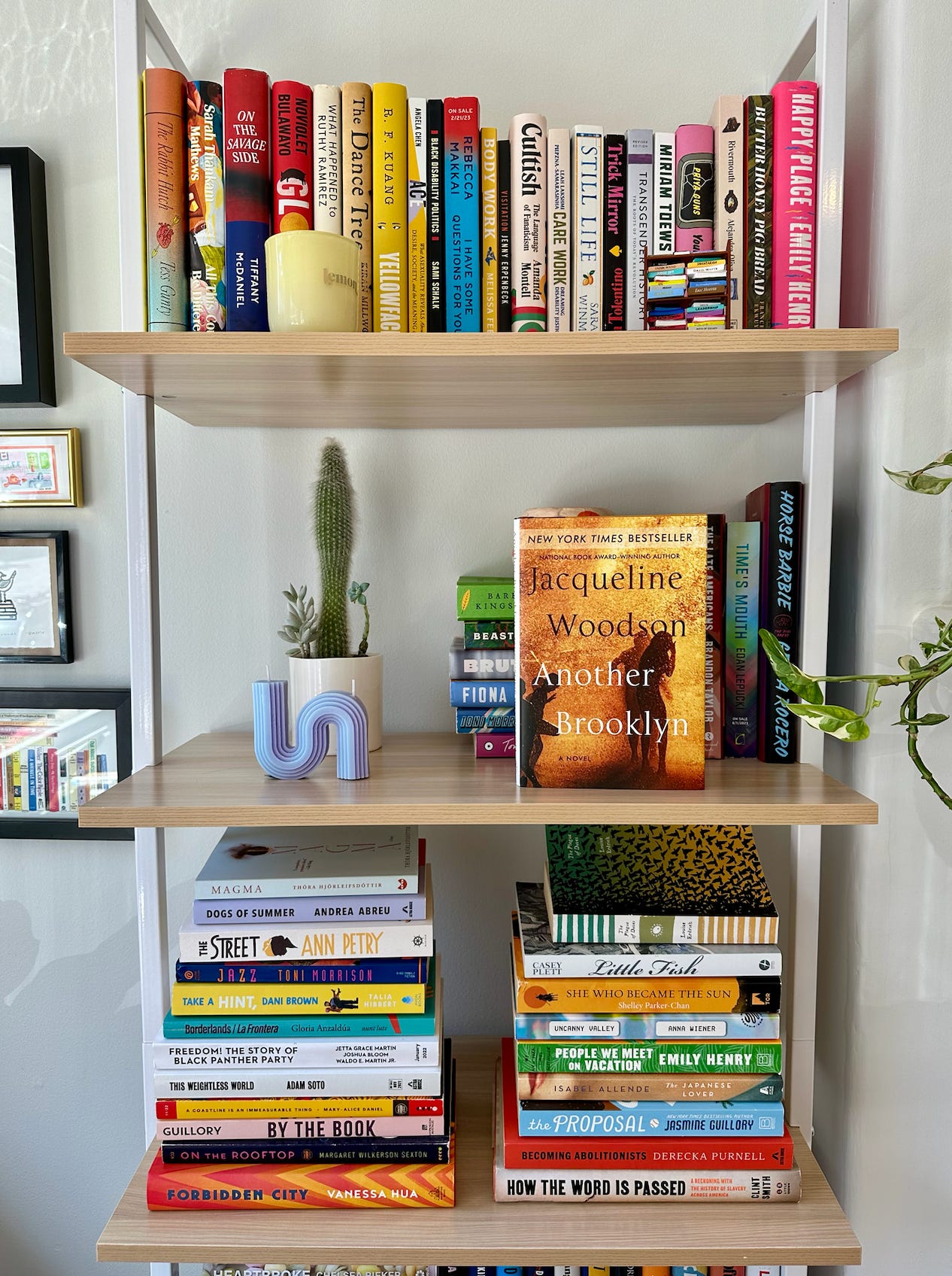

“We were four girls together, amazingly beautiful and terrifyingly alone. This is memory,” writes Jacqueline Woodson (Amistad, 2016). Another Brooklyn is a meditation on girlhood, its ups and downs, the beauty of adolescence and the terror of growth. In under 200 pages, Woodson paints a vibrant, pulsing story of girls intrinsically wound together, yet torturously alone because of societal constructs, expectations, and restrictions.

When her father moves their family to Brooklyn, August becomes enamored with the trio of girls she sees walking by her apartment window. She longed “to be a part of who they were, to link my own arm with theirs and remain that way. Forever” (Woodson, 19). Their familiarity with one another, ease, and apparent fearlessness draw August in. Yet all the while she remembers what her mom used to tell her: “My mother had not believed in friendships among women. She said women weren’t to be trusted” (19).

Despite her mother’s warnings, August befriends the threesome. And Woodson starts to paint a picture; it’s not the women August must be wary of, but society and the expectations it places on women and what those expectations force women to do. “We came by way of our mother’s memories,” she writes (55). And so Gigi begins to act, Angela to dance, Sylvia and August to become something more than what others expect of Black women. But these impressions from their mothers are not even their own, rather how society shaped them. “I can’t tell anybody but you guys,” Gigi says after she’s sexually assaulted. “My mom will say it was my fault” (58). For generation after generation, society has told women what to do, what not to do, how to be, and what not to be. “But what about his daughters,” August wonders. “What did God do with his daughters?” (23). August believes there is more—more than feeling alone, more than being cast aside as unworthy, girls being left to stomach their own pain. A purpose. But although the friend group may try to comfort one another, seeing the “lost and beautiful and hungry” in one another, they always knew “we were being watched” (38, 71).

In the end, memory paints itself as a way out, or perhaps a way forward. “I know now that what is tragic isn’t the moment,” August notes. “It is the memory” (1). Memories are fleeting, and everything we experience becomes memory. August finds comfort in knowing that what she experiences as a child is only temporary. “At some point, we were all headed home,” whether that means to a better place, a different place, or even what comes after life (170). Carving a life for herself, August pushes against society’s problematic expectations for a young Black girl living in 1970s Brooklyn. But throughout the novel are the individuals that help August get there—her therapist, her father, her brother, and yes, her friends. The CDC’s recent report on youth mental health found that 30% of girls had seriously considered committing suicide—double the amount of teen boys and up ~60% from 10 years ago. For LGBTQIA+ youth, that 30% jumps to almost 50%. Providing resources that benefit mental health, such as medical, cultural, educational, career, food, and housing resources, is critical. Another Brooklyn suggests what another life might look like, one in which such support, resources, and care are accessible, readily available, and how it is on all of us to help those in our lives make their way.

The importance of books on girlhood

When Netflix’s adaptation of The Babysitter’s Club was canceled, Kathryn VanArendonk mourned the loss of yet another show “about preteen girls that don’t oversexualize or infantilize them…not about how the world sees girlhood but rather how girls see themselves.” Depicting such stories is incredibly important, showing validation, comfort, security. And it’s easy for many to overlook such gaps, claiming they don’t exist in the first place or that they aren’t causing any harm. But the results of the CDC’s study emphasizes just how important such representation can be.

In literature, there are a number of books that can play an important role in not only young girls’ lives, but in all of our lives, whether helping us to better understand our own childhood, fight for a better society, or as a parent.

In addition to Another Brooklyn, we recommend:

Pet: “A singular book that explores themes of identity and justice. Pet is here to hunt a monster. Are you brave enough to look?”

Godshot: “Possessed of an unstoppable plot and a brilliantly soulful voice, Godshot is a book of grit and humor and heart, a debut novel about female friendship and resilience, mother-loss and motherhood, and seeking salvation in unexpected places.”

Brutes: “The Virgin Suicides meets The Florida Project in this wildly original debut—a coming-of-age story about the crucible of girlhood, from a writer of rare and startling talent.”

The Bluest Eye: “From the acclaimed Nobel Prize winner—a powerful examination of our obsession with beauty and conformity that asks questions about race, class, and gender with characteristic subtly and grace.”

The House on Mango Street: “Tells the story of Esperanza Cordero, whose neighborhood is one of harsh realities and harsh beauty. Esperanza doesn't want to belong—not to her run-down neighborhood, and not to the low expectations the world has for her.”

**Note: We receive a small commission on any books purchased through the links above.

“And as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.”

—Another Brooklyn, p38

Others’ thoughts on Another Brooklyn

“Jacqueline Woodson’s eloquent lyricism illustrates the complexities of being a Black woman. This book may be short in pages, but it is rich in the message conveyed. It is impossible to read Woodson’s work and not empathize with the characters, to not be swept away by her writing and know that you have just read an unequivocal masterpiece.” —@PrettyLittleBookshelf

“It’s not a YA book but it focuses on teenagers, it perfectly illustrates the teenage pain of no longer feeling like a child who can hide from the world.” —@FictionMatters

Thanks so much for taking the time to read! If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share with friends, and consider subscribing if you have not yet already.

We’ll be back in just a few weeks with our end-of-month issue to break down current topics in the publishing world.

Xx,

ad astra