Silken Gazelles and Platonic Love

Alharthi's latest novel emphasizes the importance of friendship

There’s a quiet beauty that runs through Jokha Alharthi’s books, one that artfully displays the strength of relationships between women—mothers and daughters, friendships, and beyond. In her latest novel to be translated into English, Silken Gazelles (Catapult, 2024), these relationships are prioritized by the writer, even if not by all the protagonists. The result is a story that challenges societal notions and preferences of love, one that displays fully why these relationships deserve just as much—if not more—attention and affection as romantic ones.

Raised as sisters, Ghazaala and Asiya are separated in their teens, not staying in touch. Years later, when Ghazaala and Harir meet in college, Ghazaala has two small children and a marriage on the verge of divorce. Harir is in the throes of obsessing over an unknown woman in her dorm, following her around campus, sneaking into her room while she is out. Both women are in search of something, a longing consuming their every day, and they search for it in the people surrounding them.

For Ghazaala, that manifests romantically, for Harir via friendship. Ghazaala feels “every kind of love there could be in the world” once her sons are born, yet “she was a mother. She was not a human being but a role,” (Alharthi, 91, 53). So she seeks out romantic love, “her desire simply to be his beloved” (194). Harir, on the other hand, questions, “What if Gazaala hadn’t married?...What if I hadn’t gotten married?...What if we weren’t mothers?” (200). She craves a life with more than romantic love, than being a mother.

“This is Ghazaala,” writes Harir in her diary, “not interested in firm ground or hard realities. Rather, she’s focused on shattered feelings and how we all use our memories to serve our own particular needs and aims” (247). But Harir is no different; both women long after a friendship they once had. “Maybe Ghazaala had been given her lot of love in childhood, and all of her miserable love affairs were nothing more than an attempt to regain the purity and depth of that early love. The love of Asiya and her mother” (255-6).

In Angela Chen’s ACE, Chen writes: “Believing that everything containing a special, charged energy must be sexual is not only simplistic; it can also shift how a relationship is perceived in a harmful way.” Our societal emphasis on romantic relationships over friendships, weighing the former as more important and exceptional than platonic love, benefits nobody in Alharthi’s story. Both Ghazaala and Harir spend their days lost in yearning—they are married, with careers, with children, both with full families. And yet, they dream of a love with “purity and depth,” something they’ve only been able to find in friendship. The shared understandings and experiences they have had in such platonic relationships are unmatched, their friendships—and its cultivation of self—proving more significant in the end.

Women in translation

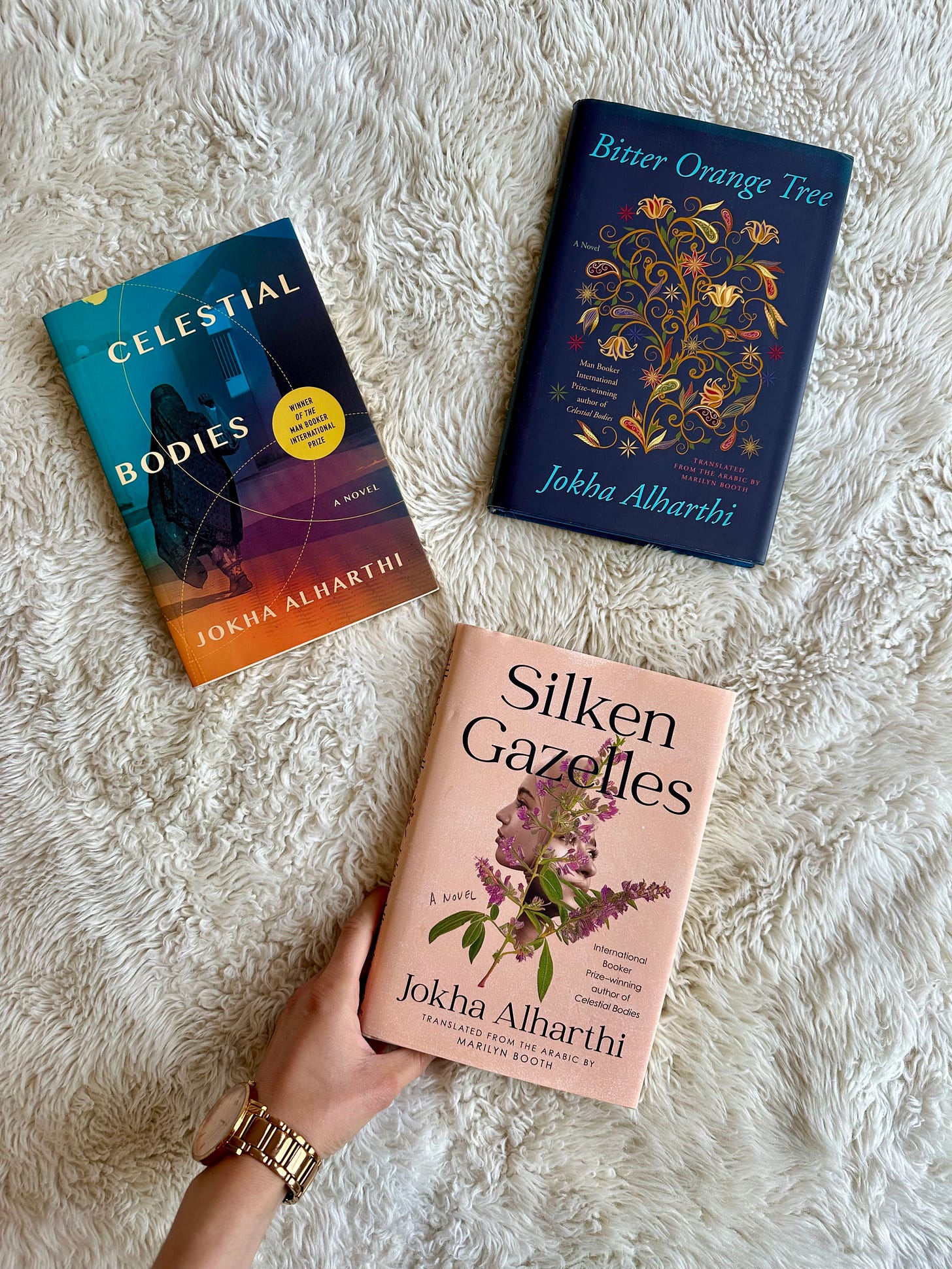

August is Women in Translation Month, which aims to highlight and elevate stories written across the globe in languages other than English, and advocate for more stories to be translated. Silken Gazelles is one of three books by Jokha Alharthi to be translated into English, her first being Celestial Bodies which received the International Booker Prize. Alharthi was also the first Omani woman to have a novel translated into English.

And while there has been some progress over the years in the number of women’s stories translated, that progress has not been nearly enough (in 2023, just 323 books were translated into English, about half being by women). Plus, some publishers find it worrisome that now readers in countries where English is not the official language are reading stories by U.S. authors and in English at increasing rates. And the stories that do get translated into English are predominantly from westernized countries, such as France and Spain, as well as eastern Asia, like South Korea and Japan. Countries across Africa and southwestern Asia, and many in South America, are largely overlooked. You can explore more on this using Publishers Weekly’s translation database.

But reading stories in translation is important - they enable us to better understand perspectives and experiences from around the globe. We’ve said this many times before, but we can’t help but wonder what people’s perceptions of the historic and ongoing situation in Gaza (and wider Palestine) would be if more stories by Palestinians were translated from Arabic. These stories deserve western publishers’ investment.

“Maybe Ghazaala had been given her lot of love in childhood, and all of her miserable love affairs were nothing more than an attempt to regain the purity and depth of that early love. The love of Asiya and her mother.”

—Silken Gazelles, p255-6

Others’ thoughts on Jokha Alharthi

“It felt like The Giving Tree; she's always beckoning the boy to come and play, come and sit, come and she'll provide and [s]he always leaves or comes back too late.” —@DogMomBookworm on Bitter Orange Tree

“The women blaze like necessary suns.” —James Wood, The New Yorker, on Celestial Bodies

If you liked Silken Gazelles, read…

Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad

Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi

Thanks so much for taking the time to read! If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share with friends, and consider subscribing if you have not yet already.

We’ll be back in just a few weeks with our end-of-month issue to break down current topics in the publishing world.

Xx,

ad astra

Currently working on a post about how the intimacy and love of platonic friendships is grossly underrepresented in fiction, at least when compared to romantic love. So timely to get this newsletter! Can’t wait to read this book! ❤️