The liminal space between motherhood and mothering

Reflections on Chelsea Bieker's Heartbroke and reproductive justice

[Dear readers: This issue contains discussions of reproductive justice and care and white supremacy.]

Located between San Francisco and Los Angeles, surrounded by various mountain ranges and parched land, and bathed in scalding heat, California’s Central Valley is often considered an “in-between,” a place one traverses through to get to the other side. Impacted by the ongoing droughts, the roads are lined with dying grass and MAGA signs. This is the environment in which Heartbroke takes place, but Chelsea Bieker’s characters remind readers of the area’s three dimensionality, its existence as something more than just a through space (Catapult, 2022).

“A mother doesn’t forget her babies, no she don’t,” writes a mother in an unsent letter to her son in Heartbroke’s namesake story (Bieker, 235). In Bieker’s second book, this time a story collection, motherhood and longing are once again at the forefront. But while Godshot focuses on the world of Lacey May, Heartbroke is full of characters. Uniting them all is the haunting of motherhood, one that stems from mothers being people in their own right, with their own desires and emotions, and one that causes the children to reap the consequences.

In Heartbroke’s epigraph, Bieker cites Denis Johnson’s short story “Dirty Wedding.” “She wanted to hurt me as only a child can be hurt by its mother.” The line effortlessly sets up the collection of stories to follow. In “Fact of Body,” Bieker writes of a mother and son living in their car by a “toxic beach,” making a living off sexual interactions with clients at the local bar (83). Bobby’s mother has dreams of being someone famous who will always have more than enough money. She makes false promises to her son about “the school…[he] would attend in the fall,” that him taking clients will be “‘one time and then never again’” (85). But eventually, Bobby “stop[s] believing in miracles, and stop[s] believing anything [his] mother told” him (86). In “Lyra,” Nev is forced into a similar position by her mother, who wants to follow “the pastor’s plan, that we would all come to live with him. We would all be his wives” (137). Motivated by her own desires, she says “Vern’s kingdom didn’t want her without [her] girls” (151). Because she wants to be with Vern, she is content with forcing her daughters into marriage. And in “Cadillac Flats,” Pretty knows “even [his mother] would look at him ashamed” if he told her about his love for another boy (206).

Yet despite the heartache these characters experience by way of their mothers, they are desperate for a connection, reluctant to leave their sides. Bobby, despite having opportunities to leave, puts on his mother’s yellow cardigan, saying “this was my only. My mother, my only” (100). Nev is unable to leave the brothel; “When my little sister Maple was setting to leave the ranch, she begged me to come with her. Said everything that happened with Mama was all over and buried and that I should move on. As if such a thing was possible” (131). And Pretty, despite thinking his mother would not understand, wants to tell her “desperately about this need” for the boy Hodges (206). Just as the epigraph suggests, the love these children have for their parents is able to break them.

In a flawed society that perceives motherhood to be a sole identity, one that cannot coexist with careers, self-growth, sexuality, etc., how is it possible for mothers to break beyond these boundaries? And, if they were somehow to do so, how could the children, shaped by the societal understanding of a mother’s role, exist independently? Not bear the consequences? In Heartbroke, they cannot. No matter what the mothers have or have not done, their children are haunted. Just as we might think to overlook the Central Valley, a liminal space Bieker has forced us as readers to acknowledge, we’ve grown accustomed to overlooking the space between simply being a mother and the act of mothering—the health care bills, the grocery expenses, the mental health support, the rent, the lack of childcare, etc. By showcasing these stories of mothers’ longing, we as readers can’t help but question what might have happened to both mother and child if the mothers received genuine care and support.

Ways to support reproductive justice

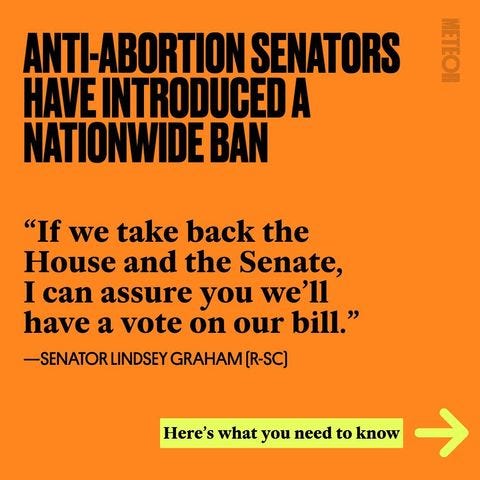

Reproductive justice is not just abortion care, nor is it just for mothers and women. Reproductive justice is about supporting individuals of all genders who can experience and/or want to experience pregnancy, and continuing that support beyond pregnancy for those who enter parenthood. Especially as senators introduce a 15-week abortion ban, our actions are essential.

For a full list of books and articles to read on reproductive justice, check out this roundup we shared in June.

We can’t stress enough how impactful ongoing donations to organizations supporting reproductive justice are. These orgs often see an increase in donations around the time of major media, but a large drop off otherwise. If financially able, set up a monthly, bi-monthly, or quarterly donation to a grassroots reproductive justice organization. Even just $5 every few months can make a huge difference.

Get involved politically:

Stay in touch with localized policies and bills from around the country and consider phone/text-banking for organizations raising awareness. This goes for both bills supporting reproductive rights and those fighting for critical support like paid parenting leave, childcare stipends/support, etc.

With midterms coming up, be sure to research which candidates on your ballot support reproductive justice and which don’t. Don’t just vote for these candidates, but help their campaigns, whether financially or through volunteer work.

Support media organizations and journalists that are supporting coverage of not just these bills, but also leaders and organizations fighting for change (we love The Meteor).

Our Resource page features a number of organizations supporting individuals in a variety of ways—many of which support parents in their efforts to care for children. Take a look and consider getting involved by way of financial involvement or volunteer support.

And whatever it is, I believe I have succeeded. I have loved her no matter what.”

—Heartbroke, p274

Others’ thoughts on Heartbroke

These reflections are on replay in our minds:

“Chelsea, baby, I don't know what you put in this collection, but I need a lifetime supply.” We couldn’t agree more, @MargauxReadIt.

“It is what makes Chelsea Bieker’s work so undeniably brilliant; she soaks a hellish landscape with more hell, only to give it soul and life.” —@TreatYoShelvess

“They are lonely, yearning for connection. Sometimes withdrawn, trying to figure out their place in the world. And they love deeply until it's too much.” —@MerylMakReads

And because we’re die-hard Bieker and @ReadKaylaRead fans, Kayla’s thoughts on Godshot (another must-read): “Lacey May does what I hope I do someday, what I hope we all do someday, and she digs it back up from that dry, dusty, glittering spot where futures go to die and she looks for somewhere better.”

If you liked Heartbroke, read…

Brother, Sister, Mother, Explorer

Thanks for reading! In a few weeks, we’ll be back with our end-of-month newsletter to dive further into critical bookish issues. If you have any questions or suggestions for reads, newsletter topics, etc., feel free to reach out via Instagram direct message or email. And if you’re a budding writer that wants to be spotlighted in our Collected Words series, let us know!

Stay tuned for next month’s book in focus, Self-Portrait with Ghost.

Xoxo,

Olivia and Fiona