The (Many) Problems With Barnes & Noble

We can’t talk about divestment without talking about the retailer

Introduction

Urgent note: Before we dive in, take five minutes to contact your representatives about Israel’s starvation of Gazans. If you can, please also donate to help get care to Palestinians.

Earlier this month, Amazon Prime Day took place, with many individuals reminding readers (and beyond) to divest from the mega retailer and its various bookish entities. That being said, we can’t talk about divesting from Amazon without also talking about divesting from Barnes & Noble.

In the world of corporate capitalism, Amazon is often the company that comes to mind. But most of us don’t have a sense of how vast their range is, especially in the book world. Owning everything from Audible to Goodreads to AbeBooks and more, the behemoth is doing its best to create a monopoly (even if it argues in court otherwise). And because Amazon is so huge—$28 billion a year in book sales, huge—it’s easy to forget about other large retailers that are also predatory and harming the book business.

Enter Barnes & Noble. Every now and then, we’ll see something online suggesting that Barnes & Noble is a “community bookstore,” or that they’re good for indies. Let’s be clear: Barnes & Noble is not a small business. They are not independently owned. And while they might not make as much money as Amazon, they are also actively working to put independent bookstores out of business, and bringing wider harm to the reading community.

In this newsletter, we’ll be diving into what exactly Barnes & Noble has done to deserve a “less than stellar” reputation, as well as why it’s important for readers to move away from supporting the corporation. Because at the end of the day, they care about profits and not readers.

A Deeper Look

Originally founded in the late 1800s, Barnes & Noble began as Arthur Hinds & Company in New York City. By 1993, the company had gone through a few iterations of its name, and became a publicly traded company. In 2019, it was purchased by the hedge fund Elliott Management and taken private once more.

When bought in 2019, Barnes & Noble had just cycled through four CEOs in five years. Elliott brought on James Daunt—founder of Daunt Books and CEO of Waterstones, both in the UK—to lead (Elliott bought a majority stake in Waterstones in 2018). In case the cycling through CEOs isn’t indication enough, Daunt came on amidst company turmoil. In 2018, they let go 1,800 full time employees, their CEO was fired because of sexual harassment, and the company reported over $17 million in losses.

While Daunt did join just before the pandemic, when the company temporarily closed ~400 stores, he’s been widely credited by the company for its so-called resurgence. In 2025 alone, the company is reported to be opening 60 new stores. Since the company is now privately owned, they aren’t obligated to release annual profits. But we can assume, given the ongoing expansion, that business is booming.

So how did Daunt turn things around? Largely through predatory, problematic decision-making. For many of you, this may not come as a surprise, given Barnes & Noble is a corporation, and especially since they are owned by a hedge fund. Profits are their priority, and capitalism too often drives corporations to make decisions that increase margins at the sake of all else—including employees and customers. The publishing industry is no exception.

For Black History Month in 2020, the company released their “Diverse Editions” campaign, popping new covers featuring Black individuals onto so-called classics. (Yep.) Of course, 11 of the 12 selected books were by white authors, featuring white protagonists. As author L.L. McKinney put it, the move was literally “literary blackface.”

In 2022, word leaked that Barnes & Noble was no longer investing in new releases, specifically those in hardcover. In a statement, Daunt said: “Barnes & Noble now works hard to improve its selection, precisely to be able to present a more dynamic bookstore. It will buy fewer titles inevitably - this is what happens if taste is exercised - but also more copies of those it seeks to champion. This will be especially valuable, when done well, for new and emerging talent.” (Emphasis our own.)

Despite claiming the decision would benefit new voices, the opposite has, of course, occurred. Independent publishers—often the presses that champion debut authors—are fed up with the company. In an interview earlier this year, Daunt claimed “the Big Five and other major houses have ‘better books’ than their smaller competitors…[making] B&N less likely to carry those titles.” While Barnes & Noble brags about cutting new inventory by 20%, many indies see this as a direct correlation to cuts from their list.

The move also has drastically impacted BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and disabled authors. And as companies reverse any commitments to DEI they may have had in place, these decisions are only more starkly noticeable. Their stores aren’t even ordering books by bestselling authors like Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Danica Nava, or not shelving them for easy discovery—let alone providing marketing support—on release day. (And these are all examples featuring established authors at big publishers!) When Daunt talks about “taste” being exercised, he of course means stories by white, cishet authors.

Such a decision echoes. When less copies of a book are sold, publishers use that data to shape future advances for not only that same author’s next book deal—if they even receive one from the publisher again—but also to problematically craft and justify assumptions about authors of the same race, sexuality, gender, etc. Advances also shape marketing dollars, impacting how much an author might earn on their book, and whether they can out earn that advance to start with.

Daunt is also very open about copying the indie bookstore model—everything from design and layout of stores to how booksellers interact with customers. And while Daunt has pushed for more full-time employees, he’s also notorious for bashing unions (which you can start to support by following them on social).

Ways to Respond

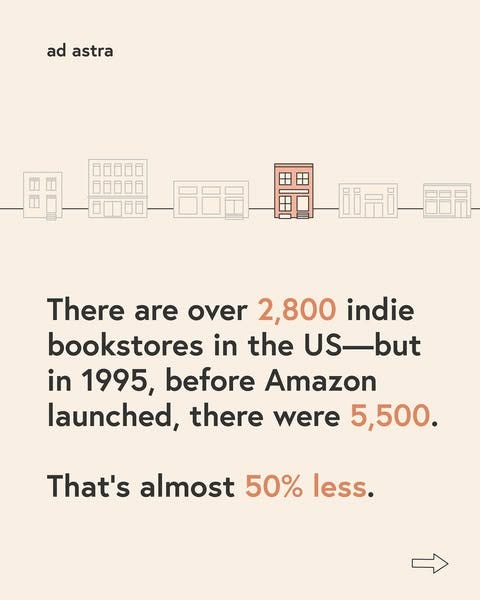

Every month, small, independent bookstores across the United States try and hit a certain number of books sold to stay open. Often, they don’t reach those numbers. Amazon is a huge factor, yes, but we can’t deny the impact Barnes & Noble has on these stores.

Earlier this year, the company announced they were opening a new location in Napa, California, a city with 80,000 people and three independent bookstores. Why would a city of this size, already with a wonderful bookselling community, need a Barnes & Noble? They also ran a sale right around Independent Bookstore Day, which has been celebrated on the last Saturday of April for years now—so no, not coincidental. And they are buying (often beloved) independent bookstores—like the Tattered Cover in Denver—keeping the original name and branding, and not telling readers about the change in ownership.

This is not about accessibility. This is not about caring for readers and hoping to get more books into their hands. This is about identifying and seizing the opportunity to take support away from these independently owned companies.

Shopping small is still often a matter of privilege, accessibility, and more. Sometimes Barnes & Noble is the only bookstore within miles and miles of us. Sometimes our indies aren’t wheelchair friendly. And, at the same time, many of us who do support Barnes & Noble could easily choose to support an independent bookstore instead, whether that means visiting the independent bookstore in person, shopping from them online, or using Libro.fm or Bookshop.org. (Not to mention our public libraries!)

We’ve written at length before about the impact of shopping small, but one of its largest benefits is that doing so directly supports your community. Whether it’s because of the taxes they pay, their donations and support for local organizations, or many being mutual aid hubs, indies are often going above and beyond to invest in you and your neighbors—something we need desperately these days.

We also can’t forget that indies are often thoroughly invested in the authors that these big retailers and publishers are completely okay with overlooking/intentionally excluding. There are indies that focus on Black authors, indies focused on disabled authors, indies focused on books in translation, and plenty more. Libro.fm’s bookstore map is a great resource—you can filter by location, how the owner identifies, etc.

Final Musings

With Barnes & Noble continuing to expand and adopting new predatory tactics, paying attention to their decisions and behavior are an important part of being a conscious reader. As readers, our responsibility goes far beyond simply reading books—we must help establish an equitable, accessible, and thriving industry beyond capitalism’s definition.

We’ll be back in a few weeks with more. In the meantime, make sure to check out our reading-themed prints for a cause, free downloads (wallpapers, templates, and more), and our exclusive downloads for newsletter subscribers (with password newsletterdownloads). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, don’t hesitate to get in touch via email, the comments below, or Instagram DM.

Xx,

ad astra